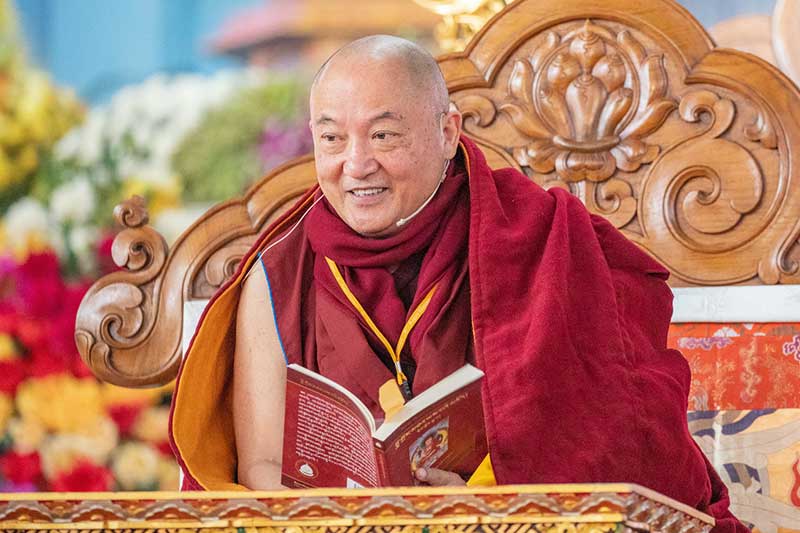

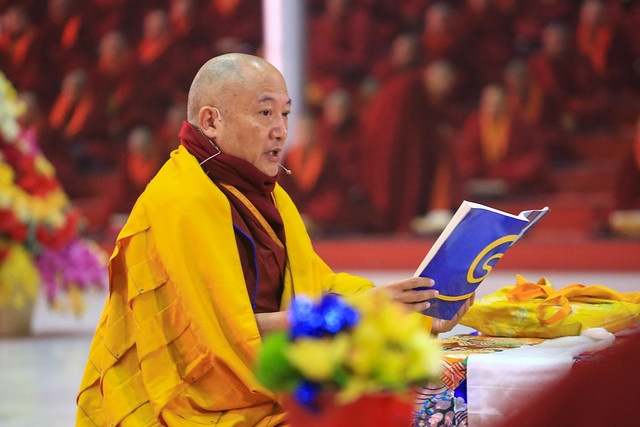

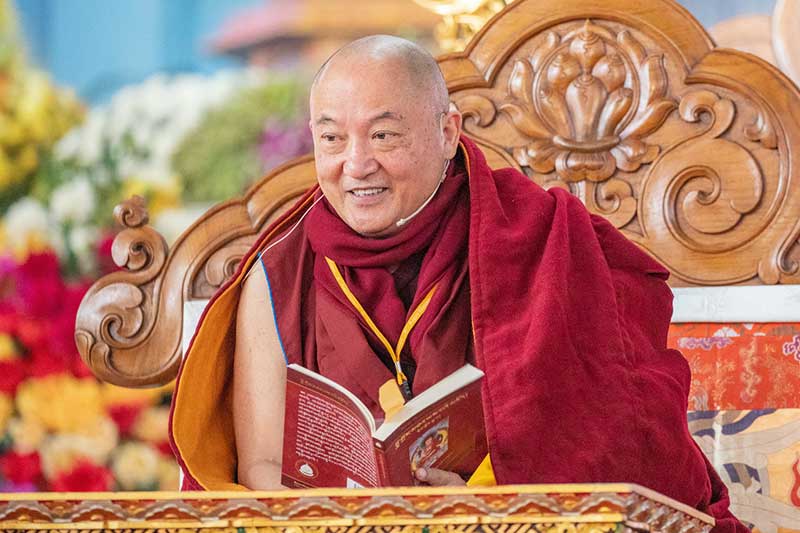

The Monlam Pavilion, Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India

January 17, 2019

After asking everyone to give rise to bodhichitta, H. E. Goshir Gyaltsap Rinpoche continued his teachings on the Seven Points of Mind training, based on the classic commentary by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye, the Great Path of Awakening. Gyaltsap Rinpoche began by reprising the Fourth Point, the Condensed Instructions on Practice for an Entire Life. Yesterday he had finished the first half on practice related to this life, and today he took up the second half, related to dying. This Aphorism 18 reads: “The mahayana instruction for the ejection of consciousness at death is the five powers. How you conduct yourself is important.”

“The time of death will come for all living beings,” Rinpoche said. “Even the Buddha, who practiced for three countless eons, had to pass away, so we, who can hardly face a little difficulty for virtue’s sake, will certainly move on to another life.”

This practice involves the five powers, which are the same as the five strengths from yesterday with a different meaning. The first one is the power of the seed of virtue, which refers to giving away everything we have without any attachment. “Usually we are attached to our possessions, but when we learn that we are dying,” Rinpoche explained, “we should gather all our possessions and give them away to the teachers, the sangha, and other good causes. We offer absolutely everything so that we can eliminate all attachment,” he said.

The second of the five powers is the power of aspiration. “In this life,” Rinpoche explained, “we pray to practice the Mahayana teachings, and in particular, those on mind training. Due to this virtue, we aspire to practice bodhichitta from lifetime to lifetime, becoming increasingly skilled so that our bodhichitta continues to increase. We pray to meet an authentic teacher, extend that wish so that it embraces all living beings, and ask the gurus and bodhisattvas to grant that it come true.”

The third power is that of remorse or repudiation. It is a specific type, referring to ego-clinging. “We see that all the problems of our past and present lives have been caused by our attachment to a self,” Rinpoche remarked. “Thinking that our ego exists when in actually it does not, is like mistaking a patterned rope for a snake. Seeing our error, we disparage our ego fixation and seek to eliminate it. Similarly, the perception that we are sick and dying is mistaken and not truly existent.”

The fourth power is strong determination. Rinpoche commented, “This refers to our thinking at the time of death, ‘In all future lives and in the bardo, may I and all living beings never be separate from bodhichitta.’”

The fifth power is that of habituation or familiarization––colloquially, “getting used to.” Rinpoche explained, “Due to our cultivating meditation on relative bodhichitta with the practice of sending and receiving, and due to cultivating meditation on ultimate bodhichitta--or residing in luminosity, the nature of the mind--we are able to one-pointedly continue these practices. This is the power of familiarization.”

Rinpoche then spoke of the physical aspect of dying and how our bodies should be positioned. “When you are dying and not terribly weakened by sickness, it is best to sit up in meditation posture with your spine straight and legs in the lotus position while resting evenly in meditation. Even if you are a little weak or sick, this still should be possible. If not, lie on your right side as the Buddha did when he passed away. If you cannot do this on your own, friends nearby can help you. As death approaches, place your awareness on your breath and while you exhale, send out all your good fortune to others. Keeping your mind on your breath with this thought is a good way to die. The best, of course, is resting in luminosity, the ultimate nature of mind itself.

“There are many impressive practices one can do when dying, but this one is the best. Even if you are doing the transference of consciousness, for example, you still need conditions like the five strengths to be present—giving away all our possessions to free ourselves of attachment, meditation on compassion for all living beings, making aspiration prayers, and so forth.”

Point Five concerns the Evaluation of Mind Training. Its four aphorisms allow us to assess how well, or not, our practice of mind training is going. Here the first Aphorism 19 reads: “All Dharma agrees on one point.” “That one point,” Rinpoche stated, “is the eradication of clinging to and cherishing a self. All Dharma agrees on this. The reason we practice Mahakala, for example, is to be freed of ego-clinging, and thereby, be able to bring great benefit to all living beings. We exhort Mahakala to engage in such beneficial activities as well, sometimes through seven or eight days of intensive group practice that includes offerings and creating a mandala. The purpose is to cut through the ignorance of ego-fixation and forget about helping oneself through meditating on deities and the mandala and benefiting others. This has the same purpose as the practice of sending and receiving found in mind training.”

If these practices are having their effect, what we notice is a reduction in our cherishing of ourselves. “This is the sign we are looking for,” Gyaltsap Rinpoche noted. “If we continue to practice and our ego-clinging remains the same, Dharma practice has not helped and has been a waste of time. In all the varieties of Dharma, the sutra, tantra, and so forth, the sign that practice is going well is that ego-clinging is on the wane.”

Aphorism 20 states, “Of the two judges, heed the principal one.” The two judges are witnesses to how we are doing—one refers to others and one refers to us. “The most important witness,” Rinpoche explained, “is the second one, ourselves. In looking at our own mind, we are the one who will see most clearly how it is. And this is important, for it is said that all Dharma comes down to looking at the mind. This is the main practice.

“And regarding our Dharma practice and conduct, we alone can know our own mind with its subtle and hidden thoughts; it is concealed from all others except the Buddha. So of the two witnesses, we rely on our own mind to check and examine its own state, to know if our Dharma practice is working or not, and if self-clinging is diminishing. Kadampa masters of the past have often given advice like this.”

Aphorism 21 counsels, “Always maintain only a joyful mind” or “A joyful state of mind is a constant support.” Rinpoche commented, “Whether we are experiencing happiness or suffering, we should always maintain a joyful outlook, and being able to practice sending and receiving makes us joyful. If we are suffering, we aspire to taking on the suffering of others. If things are going well and we are happy, we make the wish that others could enjoy happiness and good fortune, too.

“We might not have a good relationship with someone, and when they lose, we are happy. But instead we should be happy when they win for they are happy and we can be delighted that they are in a good state of mind. Similarly, if people are wealthy, famous, or highly positioned, we should think, ‘They’ve attained this through their actions and good merit and now they are experiencing the result,’ so we are happy for them. Conversely, if we get competitive and jealous about not having such riches, fame, or status, we will not feel very good, and this type of mind state also impedes our bodhisattva vow and prevents us from benefitting others.”

Aphorism 22 reads: “If you can practice even when distracted, you are well-trained.” Rinpoche explained, “In the beginning we are not very used to mind training. As we become more familiar with it, our clinging to ego lessens and this is a sign of being well-trained. In the beginning, as impure beings, we are not accustomed to the way things are and have not entered into the actual nature of mind; throughout lifetime after lifetime, we have been caught by ignorance, greed, and aversion. However, when we engage in a meditation that is in harmony with the ultimate truth and train in bodhichitta, its qualities will naturally start to reveal themselves.”

The Sixth Point of the entire text is the Commitments of Mind Training. The first of the sixteen points is Aphorism 23: “Always abide by the three basic principles.” The first of the three refers to keeping the vows of the different levels--individual liberation (the pratimoksha vows), the bodhisattva vows, and tantric samayas. Rinpoche remarked, “These all come from the one Dharma of the Buddha, and therefore, should be sustained and not decrease, so we are keeping all the vows we have taken. The second principle refers to not acting scandalously or being ostentatious about our practice. We might want to impress others with our meditation and show that we have no ego-clinging or that we are really a bodhisattva, working to reduce the suffering of others with loving-kindness and compassion. This is just the ego showing off.

“The third principle counsels not to be one-sided, which means not to limit our practice of mind training to benefitting other human beings and avoid benefitting spirits or forces that cause harm. We should regard all living beings equally and resist becoming biased. We are patient not only with those of the same Dharma tradition, race, or language, but also consider all of them equal.

“Further, some people can practice mind training when things are going well but not when they face difficulties and suffer. For others it is the opposite: they remember mind training when they are sick and suffering, but when things go well and they are happy, they become attached to that situation and proud of all the good things they experience, and forget to practice.”

Aphorism 24 counsels, “Change your attitude but remain natural,” also translated as “Change you intention but behave naturally.” Before we were caught by self-cherishing, and now seeing it as mistaken, we want to reduce it and start to cherish others more than ourselves. In doing so, we work with mind training to change our views and transform ourselves inwardly while keeping our outward behavior the same as usual and in harmony with the people around us. Other people should not suspect what we are doing because we have kept it secret.”

The next Aphorism 25 advises, “Don’t discuss shortcomings.” People might have physical defects and be missing an eye or be hard of hearing; they might have lost an arm or a leg or be disfigured in some other way. We should never speak of these problems out loud. No matter what disability they might suffer from, all living beings have buddha nature. Just as the buddhas of the three times look upon living beings as objects of their compassion, they are also supports for our practice of developing loving-kindness and compassion. Understanding this, we should only speak of the positive qualities of others no matter how they might appear.”

Continuing this line of thought, Aphorism 26 states, “Don’t contemplate others’ problems,” or “Don’t ponder the affairs of others.” Sometimes we may think that we see gurus or other Dharma practitioners and assume they are not keeping their vows or that they are breaking samaya. In this situation, we should realize that often these perceptions are based on our own afflictions, on what is impure within ourselves, which we are seeing as projected externally. If we have afflictions within our mind, we will see faults in others based on these. In the Buddha’s life story, we find Devadatta who believed he saw faults even in the Buddha.”

The next Aphorism 27 returns to working directly with the mind and encourages practitioners to begin by working with their weakest point: “Work with the greatest affliction first.” “This varies according to individuals,” Rinpoche commented. “Some are more disposed to anger, some to excessive desire, and some to jealousy. We should look into our minds and see which one of the afflictions is strongest. It is also true that the strongest affliction might vary day to day, so that one day it is jealousy, the next, desire, and another, anger. Whatever it might be, we use the relevant antidote to work with the affliction to overcome it.

Aphorism 28 states, “Abandon any hope of result.” Rinpoche explained, “Some people engage in the practice of mind training with the expectation that in the future they will see terrific results. For example, they think, ‘I’ll have a wonderful life in the future. I’ll be incredibly rich and famous and will not suffer any illness.’ This, of course, is a mistake and we should avoid projecting future benefits from what we are doing now.”

“Give up poisonous food” is the advice of Aphorism 29. “When practicing Dharma,” Rinpoche clarified, “clinging to a self or to things as being truly existent is like eating the food of Dharma poisoned by these two faults. This will harm us and keep us from realizing the goal of pure Dharma practice. We should continually meditate on the nature of selflessness and on seeing all phenomena as dream- or illusion-like.”

Aphorism 30 counsels, “Don’t be so constant.” It is also translated as “Don’t rely on old friends,” or “Don’t be so predictable.” “The meaning is not so obvious here,” Rinpoche noted. “It means that if someone has harmed you in the past, you just cannot let go of it but constantly turn it around in your mind. Some people carry a grudge (“an old friend”) around with them for a very long time, unable to part with it. We should not be like this.”

Next comes Aphorism 31, which relates to unvirtuous speech: “Don’t make malicious remarks,” also translated as “Don’t lash out” or “Don’t get riled by critical remarks.” When harsh or negative things are said about them, some people want to reply immediately in the same vein and say something awful about the other person. But instead of this, we should be able to reply with nice words and say positive things about them.”

Aphorism 32 seems to come from the Wild West, “Don’t wait in ambush.” Rinpoche explained, “It refers to harboring the wish to injure someone you do not like, thinking, ‘If I could find the right time and place to harm them, I’d do it.’ Do not wait in a narrow part of the road to ambush someone you dislike.”

Similarly, the next Aphorism 33 is about not hurting others and cautions, “Don’t insinuate, ” also translated as “Don’t strike at weak points,” or “Don’t go for the throat.” It means that even if we know something negative about another person—they have a hidden fault or have done something bad that other people do not know about—we keep it to ourselves.”

Aphorism 34 is taken from the rural world of Tibet: “Don’t shift the dzo’s load to the ox.” Since it gives very rich milk, a dzo brings a high price, whereas an ox is much less expensive. “And so we protect the dzo from something bad happening,” Rinpoche clarified, “and weight down the cheaper ox with the heavy load. It points to a situation where we are somewhat in control and do not want to burden ourselves with a problem, so we offload it onto others.”

The following Aphorism 35 states, “Don’t try to be the fastest,” or “Don’t be competitive.” Rinpoche commented, “When seeing a famous guru, we should not think for our own benefit, ‘I’m going to become even more famous.’ Or we should not think about someone on our same level of renown, ‘I’m gong to bring them down.’ We should avoid such contentious thoughts.”

Aphorism 36 is rather cryptic, “Don’t act with a twist,” but its meaning is not difficult to understand. Rinpoche explains, “We should not use these teachings of mind training to remove sickness, chase away spirits, or imply that they will make people fortunate. Do not misuse the teachings in this worldly way but employ them for their intended purpose.”

“Don’t turn gods into demons,” advises Aphorism 37. We may be an old student having practiced mind training and developed bodhichitta for many years. Considering the long time we’ve spent in the Dharma, we become proud. This is taking something good like the Dharma (the god) and turning it into something negative like pride (the demon). Avoid turning the Dharma into a cause for misdeeds.”

The final aphorism under the sixth point of commitments is number 38, “Don’t seek others’ pain as the limbs of your own happiness,” or “Don’t look to profit from sorrow.” “This means,” Rinpoche commented, “that you should not subject others to difficulties just to better your own position or get something you want for yourself. You might think that you would be benefitted if someone whose fame is the same as yours goes through great difficulty, such as losing money and becoming poor. This is another way of thinking that we should avoid.”

The seventh and last point of the entire text is the Guidelines for Mind Training. The first of these twenty-one aphorisms, number 39, states, “Perform all actions with one intention,” or “Use one practice for everything.” “Whatever we do,” Rinpoche commented, “whether we are eating, putting on clothes, or going to the bathroom, we blend this activity with bodhichitta, keeping it in mind at all times. We think that bodhichitta is all there is.”

Aphorism 40 advises, “Correct all wrongs with one intention,” or one could say, “Use one remedy for everything,” or “One practice corrects everything.” Rinpoche observed, “We might practice hard, and nevertheless, things get worse—good fortune is nowhere to be seen and problems come flooding in. We might get discouraged and think, ‘ Well, this practice of no self just doesn’t work. It’s useless.’ But we should not get lost in such thoughts; rather, we can reflect that through these difficulties, we are purifying misdeeds and obscurations.

“By experiencing a relatively small problem now, we are clearing out a greater one, such as experiencing rebirth in the lower realms with their immense sufferings. Through practice, we can be confident that a positive result will come. So when problems surface, we should be happy and delighted knowing that they are signs that a good result is coming because misdeeds are being eliminated. In this way, our enthusiasm for practice increases.”

Aphorism 41 speaks of two practices: “Two activities: one at the beginning and one at the end,” or “At the start and finish, an activity to be done.” “This means,” Rinpoche explained, “that when we wake up in the morning, we make a vow, committing ourselves to practicing bodhichitta and mind training throughout the day. At the end of the day, we review what happened and see if we were able to fulfill our commitment. How did it go? Were there signs that it went well? Or did we come under the influence of ego-clinging or the afflictions? Did our mind training weaken? If we came under that sway of the afflictions, we confess this and vow not to do it again. If the day went well, then dedicate that merit and make aspiration prayers.”

The next Aphorism 42 encourages us to develop the third perfection of patience, “Whichever of the two occurs, be patient” or “Whatever happens, good or bad, be patient.” Rinpoche commented, “’The two’ refer to happiness and misery. If it is misery we’re experiencing, reflect that it comes from (literally ‘is impelled by’) past karma. Use the experience to make aspirations that all beings be free of suffering. We can also join the suffering with the practice of sending and receiving.

“When everything is pleasant and things are going well, do not take a vacation from practice, but blend this positive experience with mind training and wish that others could enjoy the same good fortune. Especially avoid attachment to pleasurable experience.”

Aphorism 43 states, “Observe these two, even at the risk of your life.” Rinpoche remarked, “These two refer to vows related to the Dharma in general, and in particular, to those of mind training.”

“Train in the three difficulties” or “Learn to meet three challenges” in Aphorism 44 refers to three aspects of working with the afflictions. “First, we recognize that an affliction has arisen,” Rinpoche explained. “We need to recognize an affliction as an affliction. Then we overcome it through using an antidote, which is not easy, and finally we cut through the thread or the continuity that keeps it going, which is also difficult to do completely. In brief, recognize, use the antidote, and discard. We should use all three methods.”

Aphorism 45 encourages us to “Take up the three principal causes” or “Foster three key elements.” The first cause is finding a good and genuine guru. The second is making our mind workable and pliable as the Dharma teaches. The third is having what we need to practice, such as food, clothing, and a place to practice. If all of these three causes are present, be happy about it and make the aspiration that all living beings experience the same thing. If the three are not available, recognize that this situation is the result of your previous misdeeds and make the wish that all living beings will not have to experience something similar. In this way, we join both situations with aspirations and that is training our minds.”

The following Aphorism 46 states, “Pay heed that these three never wane” or “Take care to prevent three kinds of damage.” This first thing that should not decrease is respect and faith in our guru. The second is enthusiasm for Mahayana practice and mind training, and the third is maintaining the three vows. We should continuously train in all of these.”

“Keep the three inseparable” or “Engage all three faculties” is the advice of Aphorism 47. Rinpoche said, “This means that our body, speech, and mind are every second engaged in virtuous practice.”

Aphorism 48 counsels that we should “Train impartially in all areas; deep, pervasive, and constant training is crucial.” Rinpoche explained that “impartially” here means, “We should not regard as different the harm done to us or the difficulties we face depending on where they come from, whether it be humans, animals, and gods or the elements of earth, water, fire, and air. If they injure us, we should not get upset and mad at them but remain free of anger. We should never get angry at anyone, and further, we should see as equal all the different types of beings. Whatever problems come our way, we should not let anger be the response, but rather meditate on loving kindness and compassion from the depth of our being.”

“Always meditate on whatever riles you” or “Always meditate on whatever provokes resentment” is the advice of Aphorism 49. “This means,” Rinpoche pointed out, “if there is one particular person, animal or negative spirit that is always causing us trouble, we should especially meditate on love and compassion for them and work with the methods of mind training with them in mind.”

The next Aphorism 50 states, “Don’t be swayed by external circumstances.” “Some people are able to practice only when they have comfortable conditions, all the food, clothing and so forth that they want,” Rinpoche noted. “If these are not available, they cannot practice mind training. However, unmoved by external conditions, we should be able to meditate on mind training at all times.

“Right now, practice the main point” or “Practice what’s important now,” urges Aphorism 51. “The main point is not to make things better in this life,” Rinpoche commented, “but to remember that death will come and to consider our future lives when we will attain liberation and omniscience. Further, we should not be concerned with our own benefit, but that of others.”

Aphorism 52 instructs, “Don’t misunderstand” or “Don’t make mistakes.” Rinpoche taught here, “We should know that when we practice Dharma, we will face a lot of difficulties. But do not make the mistake of thinking that if you were living a worldly life, it would be easier. Business is not easy, farming is demanding, and living as a householder with a family is also challenging. Attaining the result of genuine Dharma practice, giving rise to the realizations yet to come, will take effort; however, instead of practicing, we should not look for pleasant diversions such as good food and entertainment. Do not create samsara in this way.”

“Don’t vacillate” or “Don’t switch on and off” is the advice of Aphorism 53. “This means to avoid on and off practice; one day we practice and the next we skip,” Rinpoche explained. “We should practice daily.”

In the same vein, Aphorism 54 counsels, “Train wholeheartedly.” Rinpoche encouraged, “We should train at all times and not waste even a moment.”

Aphorism 55 states, “Liberate yourself through considering and examining.” “When practicing the teachings of mind training,” Rinpoche stated, “we should be looking into ourselves, searching to see which affliction is active and being ready to respond. Even if at first it seems that we cannot do this well, analyzing the state of our mind again and again is the way we will be able to progress along the path and attain liberation.”

“Don’t make a big deal about it” cautions Aphorism 56. “Perhaps you have studied texts for a long time,” Rinpoche remarked, “and you want to impress people with your erudition. Maybe you’ve practiced mind training for many years and want to elevate yourself as someone special or outstanding. Displaying pride like this is not the practice of Dharma.”

Aphorism 57 gives us something else to avoid: “Don’t be irritable” or “Don’t be hypersensitive.” “Someone might say harsh words to you that you find offensive,” Rinpoche observed. “Your mind becomes completely disturbed, and you get so angry that you are unable to meditate on mind training. However, if no matter what others might say you do not get upset but remain stable and undisturbed, your experience and realization of virtue will not be affected.”

Aphorism 58 shows how to work with these problems: “Don’t be mercurial,” “Don’t overreact,” or “Don’t be impulsive.” These all refer to changing too quickly and easily. “You might see some behavior that you do not like or consider unfitting,” Rinpoche explained, “and you become so affected by it that you loose your composure as your afflictions come to the fore. No matter what happens, you should keep your body, speech, and mind stable.”

The final aphorism 59 cautions, “Don’t expect applause,” “Don’t expect thanks,” or “Don’t expect a standing ovation.” “Someone might have studied for many years, practiced a long time, or engaged in mind training for decades. They might harbor the wish that someone would finally come and recognize all they have done. They are looking for acknowledgment and appreciation for all their efforts. If people are not praising them, they feel disheartened. We do not want to be like this.”

With this Gyaltsap Rinpoche brought to an end his presentation of the essential points of mind training, and then he discussed the conclusion, written by Geshe Chekawa Yeshe Dorje, author of the text:

This essential elixir of instruction

Transforming the five kinds of degeneration

Into the path of awakening

Is a transmission from Serlingpa.

“At the time of the five degenerations, the afflictions are rampant and coarse,” Rinpoche explained, “yet they can be turned into the path of awakening. The elixir of these instructions has been transmitted through Serlingpa to Atisha.”

The conclusion continues:

Having awakened the karmic energy of previous training,

I was moved by deep devotion.

Therefore, ignoring suffering and criticism,

I sought out instruction on how to subdue ego-fixation.

Now when I die, I’ll have no regrets.

“Having awakened the karmic energy of previous training,” Rinpoche explained, “refers to the time before Geshe Chekawa had engaged in a lot of virtuous practice. Then he found the mind training teachings, and trained in overcoming his ego, so now he has no regrets as he has become deeply familiar with the path.”

On that positive note, Gyaltsap Rinpoche concluded his four days of inspired teaching on the Seven Points of Mind Training. [This is an edited transcript of the talk.]