A Talk to the Twenty-Second Kagyu Gunchö Regarding Matters Related to the Shedras

Given by the Gyalwang Karmapa on January 24, 2020

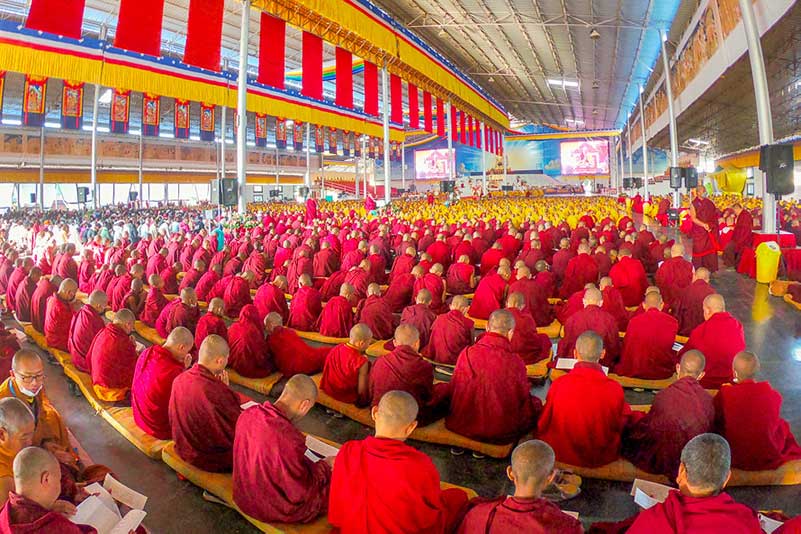

I would like to extend my greetings to all the lamas, tulkus, teachers, and students who have come to the twenty-second Kagyu Gunchö.

This Gunchö has gone very well in all respects. In particular, inviting judges from the other major lineages and holding competitive debates about the middle way and validity has produced excellent results. There was also the three-day puja for the Coemergent Vajravarahi, which is like the golden essence of the ancestral dharma of the Karma Kamtsang. Often shedra monks seem to be disinterested in pujas and rituals and to disregard them, but there was no indication of anything like that, which I think is excellent.

As you all know, in Tibet we have the lineages of explanation and of practice—the areas of study and practice. The expressions “a holder of the lineage of explanation” and “a holder of the lineage of practice” originated in Tibet. This happened because the teachings of the Buddha are divided into two parts, the teachings of scripture and of realization. These two must not be separated; they are cause and result. The division into different sections for study and practice is mainly due to the fact that when the masters of the past were practicing and meditating, they had different interests and different emphases. Fundamentally, all the dharma lineages have complete and excellent teachings of both the teachings of scripture and of practice, it goes without saying.

With the Kagyu tradition, the early holders of the practice lineage such as Marpa, Milarepa, and Gampopa primarily emphasized the teachings of practice and made meditation the core of their practice, as is clear in their life stories. However, even though meditation and practice are incredibly important, it is difficult for everyone to be a child of the mountains; wear the mist as clothes; take the loss in food, clothing, and renown; and have a strong basis in revulsion and devotion. Thus there were some who, without the pith instructions of the earlier gurus or much study of the scriptures and philosophy, went up to stay in the mountains so many people criticized and denigrated the Kagyus as idiot meditators who were like marmots in the hills. I think that this may be the reason why Tai Situ Jangchup Gyaltsen1 founded the Tsetang Dharma College. He said that the masters of the past such as Phakmodrupa were great beings who were both learned and accomplished, but his followers were too lax about their studies. Due to this, situations arose where they were incapable in both secular affairs and in dharma. He said this is the reason why he founded the Tsetang Dharma College or shedra.

In the Kamtsang tradition, the Sixth Karmapa Thongwa Donden studied the great philosophical texts from Rongtön Sheja Kunrik, who praised him highly, saying, “I have a student who is a buddha.” During his time, the Seventh Karmapa directed his student Karma Trinleypa—a great master of both the Sakya and the Karma Kagyu scriptures—to establish the teachings of study, so he founded a shedra. During that period, Karma Trinleypa taught, and the Seventh Karmapa also wrote the Ocean of Literature on Logic. This is the actual origin of a section of study in the Karma Kamtsang. Similarly, the Eighth Karmapa, as there is little need to say, wrote his great commentaries on the middle way, prajnaparamita, abhidharma, and vinaya, so that we have commentaries on all Five Great Texts. Similarly, the Ninth Karmapa also wrote abridged commentaries of the Eighth Karmapa’s works, in this way continuing and increasing the area of study.

However one cause of dismay is that during the time of the Tenth Karmapa, war with the Mongol armies caused a severe decline of the Kagyu teachings, and from then on, there were essentially no Kagyu shedras in the regions of Ü and Tsang. Later, through the kindness of Situ Panchen Chökyi Jungne, studies of the basic areas of knowledge and philosophical texts such as the Profound Inner Meaning, the Two Books of Hevajra, the Sublime Continuum, and so forth gradually resumed at Palpung Monastery in Eastern Tibet. Then during the time of the previous Tai Situ Rinpoche, Pema Wangchok Gyalpo, new editions of the commentaries written by the Eighth Karmapa as well as the Seventh Karmapa’s work on validity were published. Due to this, later during the time of the Sixteenth Karmapa, the editions that were studied were those from Palpung. All of this is the historical background. That is basically how the situation has developed.

Back in the 1980’s, when the political situation relaxed in Tibet, at first there were a few Kagyu khenpos or people engaged in study. They could only study the texts of other lineages, as they were unable to locate any texts to study our own Kagyu commentaries on the great philosophical texts. Later, the editions of those great commentaries printed in India were gradually brought into Tibet. I have heard that during that time, scholars from other lineages said, “We had no idea that you had such commentaries on the Five Great Texts in the Kagyu tradition. This is really amazing.” In any case, at the present we have those texts, and that is how this excellent situation arose.

Likewise, I believe that within the Dakpo Kagyu, the Karma Kamtsang texts on the Five Great Texts are the most complete and extensive. In addition to them, there are also the commentaries by Kunkhyen Pema Karpo. All of these are the primary texts we should study. In terms of the way we study, merely going through them in a year does not help. The more we study, the higher quality and higher level our studies will be. I also think it is important for us to also look at how other traditions engage in studies and at contemporary methods of pedagogy and learning, as well as at the examples of other peoples and cultures.

In particular, when we Tibetans study, aside from looking at the texts from our own tradition, few of us take any interest in looking at the texts by the Indian masters or by other Tibetan masters. Because we have no interest, no matter which of the texts we are studying, it is extremely difficult to get to the heart of the matter in our analysis and research. Thus, we should make our own texts the primary sources but also study the Indian texts and other Tibetan commentaries as supplementary or background sources. This is extremely important.

In particular, when we Tibetans study, our biggest fault is that we do not take much interest in history. For example, few people know who translated the root text of Entering the Middle Way, when was it translated, and how many translations are there. Thus we definitely must study the history. We need to know the history of the development of the four great philosophical schools of the Great Exposition, Sutra, Mind Only, and Middle Way and the time periods when the masters of those schools were active. I think that having a good idea of all that is extremely important.

At the same time, since we are in the twenty-first century, we need to progress and move forward along with everyone else in the world. In order to progress, I believe that we have no choice but to study other topics and areas of knowledge with contemporary methods. For example, we need to study the languages that are widely spoken in the world, such as English and Chinese. Likewise, study of science is based upon mathematics, so studying mathematics is extremely important. In terms of science, we need to study the basics of physics, chemistry, geology, biology, and so forth. This is extremely important. In addition, we must include in our curriculum the study of world history and in particular Tibetan history and the biographies and histories of the great Kagyu masters of the past. Otherwise, if we do not know the history of our forebears and the factors which molded them, we will be, as the Tibetans of olden times would have said, just like monkeys in a forest. I believe that it is important for all of us to take interest in this.

These days, I have been doing a sort of retreat and relaxing. My primary aim is to put some work into writing a commentary on the Jewel Ornament of Liberation. I spent three years researching the Jewel Ornament, and now I am collating the results of all that research and reworking it a bit. In any case, I think that having a commentary on the Jewel Ornament will be a contribution to the Kagyu lineage in general and to all who have faith and devotion in Marpa, Milarepa, and their disciples. This is what I am working on at the present. Along with this, I am also thinking of writing a text on the philosophical schools as well as commentaries on the philosophical texts. The reason is that usually I am very busy, and even if I want to write, I don’t have the time to, and it does not feel right. So now when I have some leisure, I have the thought that I might do some writing.

So at the present, for your part, you have all been able to organize this year’s Gunchö very well. I would like to thank you all for this from my heart, and I would like to say that it is my hope that the Gunchö will continue to go well in the future. For my own part, my intention is to offer service with my body, speech, and mind in every birth and all my lifetimes to the teachings of the Buddha in general, the glorious teachings of the Dakpo Kagyu that we are connected to in particular, and within those the teachings of the Karma Kamtsang so that they become widespread and excellent. I feel that my enthusiasm for this is increasing. Thus I would like to ask you all not to worry.

The Tibetan New Year is approaching, so I would like to express my wish that in the new year, all of you may be healthy, that all you do may go well, and that everything good may happen for you spontaneously and effortlessly. Thank you.

1Tai Situ Jangchup Gyaltsen (1302–64) was a regent of Tibet and founder of the Phagmodru dynasty.