Monlam Pavilion, Bodh Gaya, India

11 January, 2019

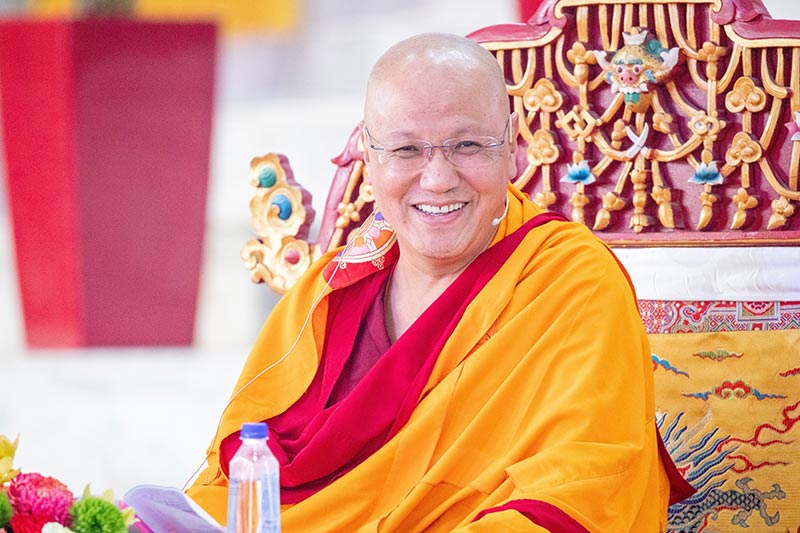

Reminding everyone to hold bodhichitta in their hearts, Kyabje Drubwang Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche began his third and last day of teaching Tilopa’s Ganges Mahamudra, the upadesha or key instructions for the practice of mahamudra. At the start of his talk, Nyenpa Rinpoche reviewed the previous verses and added new commentary. He explained that highly developed adepts could realize the whole text by simply hearing the title. Summarizing the text’s meaning at the next level comes in the traditional prostration of the translator:

I prostrate to the glorious Vajra Dakini.

Here, “dakini” refers to the entire meaning of the verses: the nature that is the ground of mahamudra and the nature that is the path of mahamudra; when these two manifest, the fruition of mahamudra appears. In this way the dakini symbolizes the realization of ground, path, and fruition. According to the teachings of the Kalachakra, “dakini” points to Prajnaparamita, the great mother of all the buddhas.

Another way to express this is that no phenomenon transcends the fundamental nature. When the great mother Prajnaparamita manifests, we can see the true nature of all phenomena appearing as samsara and nirvana. Female deities, such as Tara and Vajra Varahi, are displays of the great mother’s form. Here the vajra symbolizes the mahamudra of the definitive meaning, which is represented here as the glorious Vajra Dakini.

The Student and Teacher

The first verse of the Ganges Mahamudra describes students who could practice mahamudra and they have four characteristics. (1) Intelligence is the most important as it allows one (2) to endure hardship, (3) to see the qualities of the guru and therefore have respect, and (4) to bear the suffering that comes with practice, as we engage our body, speech, and mind fully in listening, reflecting, and meditating on the teachings. How we act depends on the conditions around us, and our intelligence allows us to know what makes a condition positive or negative. This is not a mere intellectual knowing but based in the experience of practice.

Since Naropa had all four of these qualities, Tilopa gave him all the pith instructions on the banks of the Ganges, saying to his disciple, “I have no human guru. In coming to your own realization, you’ll realize the guru.”

Today we can meet teachers and discuss the Dharma with them for hours. But this might not be the good fortune we take it to be if we do not develop the power and strength of our meditation. We should be able to go through difficulties. Meeting the Dharma is not like finding gold by chance. It comes from gathering the two accumulations and from karmic connections that extend back for many generations. If we are constructing a tall building, we need a stable foundation. To meet a real guru we need genuine conviction.

Meditation and post-Meditation

The next verse reads:

Mahamudra cannot be shown,

Just as who can show space to whom?

Likewise, there’s nothing to show in the nature, mahamudra.

Relax and rest in the unaltered basic nature.

If the bonds are loosed, there’s no doubt you’ll be freed.

These lines show us how to practice and become free. Yesterday we talked about not being distracted while mind looks at mind. Distraction is a troublesome situation brought about by an impure mind. When we come to meditation, we should be relaxed: the mind that looks is not separate from the mind itself: whose nature is luminosity and emptiness inseparable. With gentleness, we rest within that in equipoise. When we arise from it, all that we do comes from being settled into the basic nature.

At our stage of practice, however we separate meditation and post-meditation, because once up from the cushion, we forget the experience of our meditation, and therefore, cannot blend it together with our ordinary activities. If this separation happens, we will not benefit from the intensity of our meditation. So contrary to our usual tendencies, we should continue to bring meditation into practice, to the point that there is no difference between meditation and the period afterward. Then we can take ordinary activities as the path and our meditation will increase in strength.

Whether this happens or not, depends on our post-meditation practice. If we lose ourselves to the mundane mind of our daily activity, post-meditation will not benefit our meditation. For this to happen, we first rest one-pointedly on an object, and then in post-meditation we carry that onto the path. Prajna or wisdom does not only mean resting one-pointedly. The Nyingthik tradition of pith instructions, for example, incorporates into daily practice questions based on the second chapter of Nagarjuna’s Fundamentals of the Middle Way. This chapter deals with motion, so we are asked, is there someone who is moving? In which direction are they going? East? North? West? South? And so forth. These questions move our mind back into emptiness and to seeing how meditation and post-meditation are not different.

Of course, when a beginner enters post-meditation, they must employ carefulness and awareness to make sure that what they do is embraced by the experience of meditation. For the advanced practitioner, the Fundamentals of the Middle Way shows how to blend meditation with post-meditation: They realize that as things arise, they are liberated. If we do not know this, thoughts become maras (obstacle makers) for us and we will not realize the result of our practice. The union of meditation and post-meditation happens due to our realizing that thoughts are liberated as soon as they arise.

Relaxing and Sustaining

The fourth line “Relax and rest in the unaltered basic nature” refers to abiding in suchness or the basic ground. When we recognize that this is an inherent quality we have within ourselves, we have arrived at the level of liberation upon arising. If we know this, there is no need to remove boundaries, for example, between meditation and postmeditation, and we will not have to rely on scriptures. This knowing comes from our experience. Saraha said that if we realize our own suchness, even a distracted mind arises as mahamudra. This is the self-liberation of thoughts.

We can meditate and arrive at the place where all thoughts cease, and we may think that it is not easy to take this into our daily lives; in actuality however, this is not so difficult. What is hard is taking ordinary appearances onto the path. When we are meditating, we can feel as if we are free of desire or hatred; however, if we do not know how thoughts are liberated upon arising, the poisons will surface when the circumstances that stimulate them come about. In a contemporary way, one could say, “we lose it.” The real practice then is not being swayed or affected by circumstances but sustaining our awareness of mind’s nature. This allows all thoughts, all that happens, to be freed as they appear. If we can do that, we are a yogi. Until then, we need to be careful and set up the sentry of mindfulness. Ideas will continue to create problems for us until we have really cultivated the fact that they do not exist. Tilopa counsels us:

Relax and rest in the unaltered basic nature.

If the bonds are loosed, there’s no doubt you’ll be freed.

How to Sustain Practice

Tilopa continues:

Just as when you look in the center of space, seeing stops,

Likewise, when the mind looks at mind.

Thoughts cease and unexcelled enlightenment is achieved.

These first lines explain how to sustain practice, which does not mean to sit distracted by thought with our eyes and mouth open. This would be like imagining porridge to be gold. We should practice so that the six objects of our senses (forms, sounds, etc.) are released as they arise and thereby transformed into aids to our practice, which becomes all the stronger for dealing with them directly and not being swayed. We simply rest without altering it. In this state, meditator and meditation are not separate from mind’s nature, so we can sustain our meditation and not be affected by circumstances.

We realize that thoughts are the dharmata (the nature of phenomena). Afterward, when many thoughts arise, they simply strengthen our meditation; if we want the immense fire of realization, we need a lot of wood. This is what is meant when it is said that thoughts are really kind. If we think that thoughts are an obstruction, we have failed in meditation by not bringing the variety of conditions or appearances onto the path.

Just as clouds of mist dissipate in the expanse of the sky,

Not going anywhere, not staying anywhere,

So is it with the thoughts arising from your mind.

Seeing your own mind purifies the waves of thought.

The nature of space transcends color and shape,

Neither stained nor changed by black or white.

Likewise, the essence of your mind transcends color and shape,

Unpolluted by black or white qualities, misdeeds or virtues.

These verses speak about appearance and emptiness inseparable; when we see this, we are liberated from taking things to exist or not. At this point, conditions cannot affect our minds.

Mind and Mind Itself

The term for “mind,” understood in this context of mahamudra as “the nature of mind,” is often written as sems nyid, or mind (sems) itself (nyid). The nyid is an emphatic particle indicating that mind is nothing other than itself; it is suchness (de bzhin nyid), or in a translation based on the meaning, “the mind remains as it is in itself.” The mind itself is the basis and essence of all appearance. It is crucial to distinguish between (relative) mind and its (ultimate) essential nature or between mind and pristine awareness. Knowing mind itself, we can free ourselves from even the most subtle dualistic thoughts that arise as samsara due to our grasping onto them as real.

Samsaric phenomena come about through the mind; if we can realize this, that is nirvana. It all comes down to whether we realize the nature of our mind or not. And this realization happens only through wisdom; it does not come about through thoughts that conflate a word with some meaning, because these are not connected to the true nature of things that wisdom alone can see. Resting in this nature is the way to sustain mahamudra. In brief, all phenomena are mind and mind is empty; rest in the unelaborate.

Just as the bright, clear essence of the sun

Cannot be obscured by the murk of a thousand eons,

Likewise, the luminous essence of your mind

Can’t be obscured by eons of samsara.

Though space is given the appellation “empty,”

There’s nothing in space that can be described as such.

Likewise, though mind is described as luminous,

There’s nothing to give a name, saying it’s like this.

Therefore, the nature of mind has always been like space.

There are no phenomena at all not contained within it.

Let go of all bodily acts; sit naturally at ease.

Not speaking, your speech is empty sounding, like an echo.

Don’t think of anything with your mind; look at the dharma to resolve.

The body has no essence, like a bamboo stalk.

The mind, like the center of space, transcends conception.

Neither taking nor leaving, rest relaxed in its nature.

“Look at the dharma to resolve” means that thoughts are liberated upon arising. It could also mean, “look directly at the dharma.” (Dharma or chos in Tibetan has many meanings, among them “the nature of mind.”) The term “la da ba” (la bzla ba) comes from the tradition of Dzogchen or the Great Perfection and can be translated as “resolve,” “cross over,” or “leap.” In this case, it refers to the inner confidence we have of our realization. We have completed it—fearless like a lion springing from one side of the abyss to another. We are confident that everything can be brought into self-realization and that view, meditation, and conduct are inseparable.

Here we are getting close to the perfect practice of the pith instructions. Not all meditation is like this, so it is important to understand our level of practice. We need to receive and retain many pith instructions about the mind and put them to use. For example, the first three lines of the last verse above (beginning “Let go of” and ending “to resolve”), give an instruction on three ways of resting in the true nature through body speech and mind. Practicing like this leads to the next two lines.

Free of Aims, Concepts, and Wanting

When mind has no aim, that is mahamudra.

When you are habituated to that, you will achieve enlightenment.

Knowing that everything is liberated on arising, we realize that mind has no aim.

(Yesterday we stopped here.) [“Aim” here translates te so, (gtad so), which can also mean, “object,” “concept,” “target,” basically anything that a relative intellect (blo) focuses on. Primordial wisdom or awareness is free of this, i.e., it has no objective referent, it is gtad so (focus) med pa (without).]

Therefore, if we have some conception about the dharmadhatu, the expanse of all dharmas, we have not realized the view. The same is true for meditation and conduct. In sum, we must be free of a view with assertions, meditation with a focus, and conduct with preconceptions. Therefore, the next verses state:

You will not see luminous mahamudra

Through recitation of mantras, the paramitas,

The vinaya, sutras, or other baskets of scriptures

Or through your own texts and philosophical tenets.

When wishes arise, luminosity is unseen, obscured.

Keeping vows and samaya conceptually violates the actual.

Wishes here are like assertions or opinions, and as long as we have these, whatever we are doing, such as keeping the vows of individual liberation or the bodhisattva vows, becomes merely conceptual. This type of practice cannot help us to achieve a high level of meditation because conceptualizing keeps us away from our inner nature. The vows a yogi keeps are free of mental engagement or intention—beyond vows to be kept and a keeper of the vows—and these vows are an aid for realizing the nature of mind. It is also said that during the creation phase of meditation, if we mentally project the visualization, this will not bring us into realizing the view.

For the beginner, vows are necessary as they help to restrain the gates of the sense faculties when they cannot be restrained by carefulness, awareness, and mindfulness. After all, the Buddha first taught discipline, then samadhi, and finally wisdom. The vows related to body, speech, and mind restrain our mind so that it does not come under the sway of distraction and remains protected from inappropriate thoughts. During the Mahakala puja, we request that he protect us so that our mind does not come under the influence of distraction or unsuitable thinking because this will prevent us from realizing the nature of mind and resting in self-liberation.

The texts speak of a bhikku whose body is controlled by vows as excellent. He has the ability to stay up the entire night practicing meditation. This is quite a profound level of meditation.

Free of Mental Engagement

Not engaging mentally, free of all wishes,

Self-arising, self-subsiding, like ripples in water—

If our mind can rest without mental engagement, it can come into nirvana, because it is not affected by the stains of seeing samsara and nirvana as dual—it transcends existence and peace. Like a drawing on water, thoughts come and go naturally. They are freed as they arise, so there is no need of methods to work with them. When we recognize the nature of a thought, it subsides into suchness, so actually, the more thoughts we have, the more our practice is benefited.

If you don’t transgress the nonabiding, unobservable nature,

You will not transgress samaya. This is the lamp in darkness.

“Nonabiding” means that mind itself, our inward mind, does not arise, stay, or cease. No matter how much it arises, the mind has no basis that allows it to stay. Awareness is free of support. The Treasury of the Dharmadhatu states that since mind has no support it is nonabiding. If we examine the true nature, we cannot find any foundation for mind. Since there is no basis for anything to rest on, there is nothing to observe either. This samaya is the one that we should keep. If we do not transgress it, it is a lamp in the darkness.

Gotsangpa on Samaya: Faults and Their Nature

Gyalwa Gotsangpa (1189-1258) was a great master in the Drukpa Kagyu tradition, who composed a famous pith instruction, known as the Circlings of a Lance in Space. Between an opening and closing stanza, eight verses speak to eight main topics in three ways. The topics are view, meditation, conduct, fruition, samaya or vows, compassion, relations, and activity. If we practice the true meaning of Gotsangpa’s verse on samaya, it comes out to be the same as Tilopa’s verse that we just read. Gotsangpa’s verse on samaya runs:

Not stained by faults and downfalls,

The experience of flawless clarity/emptiness,

And self-importance abandoned—

Three ways that samaya is free

Like a lance circling in space.

The first line means that mind’s nature has never been stained or obscured. Knowing this is like having a firm seat, a stable place, so we are comfortable whatever we might do. Without a steady basis, we can be unbalanced and fall. But if we are firmly centered in our own ground, we can move and act freely without worry. So first we need to know the true nature of our mind, its very foundation, and be completely convinced that it has no faults. This confidence is very important.

When we speak of a mind free of stains, it refers to a special mind, the nature of our mind, and not our usual one. Our regular mind operates through the six consciousnesses and their objects. For example, it becomes attached to beautiful forms and doesn’t like ugly ones. Through the influence of an appearing object, ordinary mind loses its own power, and this allows faults and downfalls to happen. We have to confess these, which we wouldn’t have to do if we had remained within mind’s nature.

Right now we have faults, so we need to confess them by regretting what we have done, reciting mantra, resolving not to repeat our mistake, and so forth. This is a beginner’s way. We need to know our level of practice and apply what fits our mind since there is no all-purpose practice that applies to everyone. A yogi knows that faults and downfalls come through thoughts and that all thoughts are naturally liberated, so faults and downfalls do not essentially exist. To take it a step further, the yogi also knows that the individual person does not ultimately exist either. If we can realize this, that is the best way to keep samaya; however, this comes with a high level of realization. We must be careful not to fool ourselves or others in thinking that our realization is higher than it is.

In sum, this first line of Gotsangpa’s verse on samaya is taught from the perspective of mind’s nature, in which there is no stain, no fault, and no downfall. If faults and downfalls were by nature nonexistent, what would be the basis for imputing a stain? So that we are not caught up by words, we should also remember that “the mind’s nature” is merely a label, a name that’s been posited, a convention agreed upon. This line, then, presents samaya from the ultimate point of view.

Meditative Experience

The second line of the verse states, “The experience of flawless clarity/emptiness.” When we meditate, experiences arise and they are signs that precede realization, just as warmth comes before a fire. They do not remain, however, but come and go like clouds appearing and disappearing. But when realization comes in their wake, it is stable like the sun and moon. So while the experience is happening, if we can connect and remain within its depths, realization does arise.

In sum, meditative experiences fade away and realizations remain unchanging. While we are practicing mahamudra, experiences of bliss, clarity, and nonconceptuality will arise, but these are passing experiences and not realization. They do not mean that we have realized bliss or clarity or emptiness. These are merely precursors to the realization of mahamudra and not mahamudra itself.

“Flawless” in the second line means that the nature of mind is free of flaw, but ordinary individuals are at first blemished by stains. The nondual nature of the experience, however, is not affected by any flaw.

Getting Over Fixation on Oneself

The next line of Gotsangpa’s verse is essential: “And self-importance abandoned.” A good deal of the time, we are focused on ourselves, wanting to be celebrated and famous, thinking that all should go well for us, and that we have to get rid of faults and manifest good qualities. We are so bound up in ourselves that we focus on wanting everything good for us alone. When we practice the teachings, our minds are preoccupied with expectations; in meditation, we are fixated on our desires. View, meditation, and conduct—our whole life is all polluted by our thoughts. Gotsangpa is telling us to throw away this sense of self-importance and excessive desires, to toss off our fixation on ourselves, on friends and enemies, on hopes and fears. Give up the three realms of desire, form, and formlessness. Let them all go.

In the Dzogchen tradition, there is a phrase, “move relaxed in open space,” (bya yan lhod pas bgros) and we find, for example, in Longchenpa’s Treasury of the Expanse of Phenomena, the line, “Free of the three times, move relaxed in open space.” It means that whatever we do has a relaxed and spacious feel to it. (The opposite would be, for example, wearing uncomfortable clothes that are too tight.) We let whatever happens, happen since we are free of hope and fear or doubt. We have let fixating on self-importance go. Now we can see that “move relaxed in open space” points to Gotsangpa’s ultimate samaya that “is free, like a lance circling in space.” These are profound words filled with blessing.

Having finished his commentary on Gotsangpa’s stanza, Nyenpa Rinpoche then turned to the next verse of Tilopa’s, which illustrates our practice when we find the ultimate samaya described by Gotsangpa:

If, free of all wishes, you do not dwell in extremes,

You will see the dharmas of all the scriptures.

Settling into this nature, you’re freed from the prison of samsara.

Resting evenly in this nature incinerates all misdeeds and obscurations.

This is taught to be the lamp of the teachings.

If we can rest in a practice like this, we will have attained the two types of wisdom: the wisdom that knows the nature of all phenomena as they are and the wisdom that knows the extent of all phenomena. Resting in these two, free of all wishes or assertions is the lamp of the teachings, and thereby, we are able to understand all that the scriptures reveal.

In the phrase “settled into this nature,” “settled” translates the verb zhol wa (gshol ba) which can also mean, “to arrive in,” “to come to,” “to alight or descend from a vehicle,” “to flow into,” “to land,” “to reach,” or “to get to.” What is it that we settle or flow into? Once freed from wanting, we can rest in the abiding nature of mind. Putting aside our hopes and wishes allows our practice to arise and we come to the nature of the mind.

Another way to see how we reach the nature of the mind is looking at view, meditation, and conduct. Our view is free of anything that is superimposed, free of saying that something exists when it does not. We have reached the stronghold of meditation that is stable. And our conduct, free of attaching to the characteristics of things, accords with our view and meditation. We arrive at the nature of mind by practicing this kind of view, meditation, and conduct, which has not deteriorated in any way.

This practice is continuous, so if we are lighting a stick of incense or a butter lamp and remain within this view, meditation, and conduct, that will bring us into realizing the nature of mind. This way, all our activity related to body, speech, and mind becomes a practice leading to abiding in the nature of mind.

We might have separated the accumulation of merit in post-meditation practice from the meditation of mahamudra. However, if we receive a guru’s blessing and pith instructions that allow the nature of the mind to manifest and put them into practice, our accumulation of merit and purification of obscurations will be connected to our meditation. All that we do, all movement of our body, speech, and mind becomes “a friend of our practice” and leads to being settled into mind’s nature.

Beyond Texts and Ritual

When this happens, we will be able to see into all the scriptures—the vinaya, the sutras, the abhidharma as well as the ordinary and extraordinary tantras. We will not need to look at each page of the text, deciphering the meaning of the words, figuring out the complicated outlines with their many divisions and subdivisions, or memorizing the meanings of the terminology. We do not have to work with each one of these separately. As Aryadeva states in his Four Hundred Verses:

Whoever sees one thing

Is said to see them all.

The emptiness of one thing

Is the emptiness of them all. (191)

If we can realize the deep inner nature of one phenomenon, we can realize that nature in all phenomena. If we can release one, they all are released. If one is liberated, then there is no need to liberate all—they are automatically liberated. This being settled into self-liberation is the special “technique” of the great meditators. Liberation is liberated right within itself. If we had to liberate, or realize separately the individual nature of each phenomenon, it would be endless. The meaning we’ve been discussing in Aryadeva’s verse is the same as that of Tilopa’s we have just considered:

If, free of all wishes, you do not dwell in extremes,

You will see the dharmas of all the scriptures.

Settling into this nature, you’re freed from the prison of samsara.

Resting evenly in this nature incinerates all misdeeds and obscurations.

So we do not need to gather firewood and a rich variety of offering substances to perform fire pujas with all their chanting and bustling about. They will not lead to liberation, because our minds are caught in the relative truth, focusing, for example, on the fire or wood as having self-existing characteristics and being real. We will not realize the key point of practice if our minds are tied up in such mind-numbing confusion, though it can be pleasant on a cold winter day to sit near a warming fire.

One Point Is All We Need

If this one point of mind’s nature is realized, then all obscurations and negativities are burned up. Or one could say that phenomena subside into their natural ground. As Gotsangpa wrote:

Not stained by faults and downfalls,

The experience of flawless clarity/emptiness.

If we have realized the single point, we are not stained by faults and downfalls. There is no need to establish or grasp on to the experience of clarity and emptiness inseparable. It is not necessary to deliberately get rid of self-importance. If we know that the pleasurable objects of the senses are self-liberated, and further that the six consciousnesses are self-liberated, and if we are also free of attachment, our self-importance is naturally liberated. This happens through the strength of our meditation and not through wanting to toss it away, wishing we did not have it, thinking we need to tame it, and so forth. When we see the essential nature of things and truly settle within it, no matter what happens, we can remain there. When we are free of wanting, riches will make no difference to us. If we have seen the nature of one object of consciousness, seeing hundreds of thousands f pieces of gold will not affect us and hundreds of thousands of pleasurable objects pose no danger. We have seen mind’s nature, so self-importance with all its ramifications no longer matters. This verse of Tilopa’s is deep:

Resting evenly in this nature incinerates all misdeeds and obscurations.

This is taught to be the lamp of the teachings.

The lamp of the teachings is realizing the essential nature that we have just discussed. With this, Nyenpa Rinpoche concluded his morning talk. [This report is an edited transcript of the teachings.]